Once State-Extirpated Piping Plovers Nest in Pennsylvania

Absent as a Pennsylvania breeding bird since the mid-1950s, two pairs of federally endangered Great Lakes piping plovers returned in 2017 to nest in the Gull Point Natural Area at Presque Isle State Park in Erie County.

Current Status: The piping plover (Charadrius melodus) is extremely rare in Pennsylvania and highly imperiled across its North American breeding range. Three geographically distinct breeding populations are recognized, each federally listed and protected under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Returning to nest once again in Pennsylvania in 2017, the first time since the 1950s, piping plovers are managed as part of the federally endangered Great Lakes population, the smallest and most vulnerable of the three populations. The other two populations, Atlantic Coast and Northern Great Plains, are federally threatened. All migratory and wintering piping plovers are federally protected as threatened species. In addition, piping plovers are safeguarded through the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 and Pennsylvania's Game and Wildlife Code. Current state listed as endangered, the piping plover is a highest-priority Species of Greatest Conservation Need in the

Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan.

Population Trend: Historically, several hundred pairs of Great Lakes piping plovers nested on every Great Lakes shoreline. Until the mid-1950s, about 15 breeding pairs nested regularly on Gull Point at Presque Isle State Park, Erie County. When the Great Lakes population was granted federal protection under the Endangered Species Act in 1986, only 17 breeding pairs remained and all were restricted to the state of Michigan. In 2017, the Great Lakes population grew to 76 breeding pairs found in four U.S. states and Ontario, Canada. Piping plovers are rare but regular fall and casual spring migrants at Presque Isle State Park. In 2011 and 2012, historic nesting habitat in the Gull Point Natural Area was re-stored through federal funding. Piping plovers have briefly visited nesting habitat at Presque Isle State Park during spring and fall, renewing hope for the return of this species to Pennsylvania. Indeed, two pairs successfully nested in the Gull Point Natural Area in 2017. 2017 marked the first nesting on every Great Lake since 1955.

Identifying Characteristics: This sand-colored shorebird just larger than a sparrow is found exclusively along shorelines of large water bodies, such as Lake Erie or, on extremely rare occasions, the Susquehanna or Delaware rivers during migration. Like other plovers, the piping plover feeds along the shoreline in a series of short stops and starts as it pecks for aquatic insects and worms. It can be distinguished from its more familiar cousin, the killdeer (Charadrius vociferous), by its shorter stature, orange legs, single breast band and orange bill with black tip during the breeding season. Additionally, piping plovers can be identified by their subtle two-note “peep-lo” call, typically heard before this well-camouflaged shorebird is seen. In contrast, as its scientific name suggests, killdeer are noticeably louder birds, dramatically proclaiming their name (“kill-deer”) as they run or fly through generally less selective habitats. Killdeer are commonly found in developed landscapes such as baseball fields, flat gravel roofs, and along driveways, although they can also be found along shorelines. Identification of migratory piping plovers during fall can be more challenging because the orange bill with black tip becomes all black and the breast and head bands molt to grey and white feathers. Luckily, the orange legs are still visible, albeit a muted tone.

Identifying Characteristics: This sand-colored shorebird just larger than a sparrow is found exclusively along shorelines of large water bodies, such as Lake Erie or, on extremely rare occasions, the Susquehanna or Delaware rivers during migration. Like other plovers, the piping plover feeds along the shoreline in a series of short stops and starts as it pecks for aquatic insects and worms. It can be distinguished from its more familiar cousin, the killdeer (Charadrius vociferous), by its shorter stature, orange legs, single breast band and orange bill with black tip during the breeding season. Additionally, piping plovers can be identified by their subtle two-note “peep-lo” call, typically heard before this well-camouflaged shorebird is seen. In contrast, as its scientific name suggests, killdeer are noticeably louder birds, dramatically proclaiming their name (“kill-deer”) as they run or fly through generally less selective habitats. Killdeer are commonly found in developed landscapes such as baseball fields, flat gravel roofs, and along driveways, although they can also be found along shorelines. Identification of migratory piping plovers during fall can be more challenging because the orange bill with black tip becomes all black and the breast and head bands molt to grey and white feathers. Luckily, the orange legs are still visible, albeit a muted tone.

Biology-Natural History: Piping plovers begin arriving on their breeding grounds by mid-April. Males typically arrive before females to establish a territory, usually in the same location as the previous year, if the male had successfully found a female. The same female will likely join him if they successfully raised young the previous year. Following a brief courtship of aerial flight displays, scraping, and pebble-tossing, egg-laying begins in a small, bowl-shaped, pebble/shell-lined scrape in the sand. The female lays one egg every 1.5 days until the full clutch, typically four eggs, is complete. Incubation begins after the fourth egg is laid. The adults trade incubation duties for 28 days until hatching. Plover chicks can walk and feed themselves almost immediately after hatching (i.e. precocial), gleaning insects as they dart around the shoreline like cotton-balls with legs. For the first week, chicks are not able to regulate their body temperature and must be brooded (sheltered) by either adult to survive. Both adults tend to the chicks, leading them toward food resources and away from harm, until the chicks can fly in about 30 days.

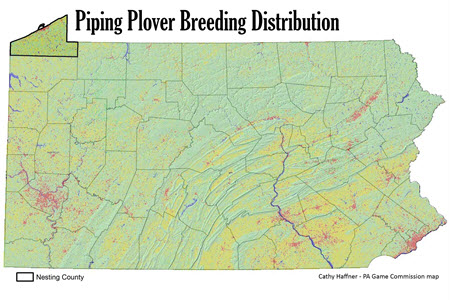

Preferred Habitat: Great Lakes piping plovers nest on wide, sand to cobble beaches with little vegetation and a long distance to the tree-line, affording some protection from predators. The only breeding habitat for piping plovers in Pennsylvania is along the shoreline of Lake Erie at Presque Isle State Park, which has been designated as “critical habitat” by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In migration, piping plovers have occasionally been observed away from Presque Isle State Park; historically along the lower Susquehanna River shoreline at Conejehola Flats in Lancaster County (Audubon Important Bird Area #56) and most recently at Shawnee Lake at Shawnee State Park in Bedford County. These “refueling” sites, with moist soils containing a high abundance of aquatic invertebrates, are extremely important to allow shorebirds to regain energy during long migrations. All three populations of piping plovers winter along the southeastern Atlantic coast from North Carolina to Florida, west through Texas, and in parts of Mexico and the Caribbean, where they peck marine invertebrates from mudflats and moist sand.

Reasons for Being Endangered: Piping plovers nest on coastal beaches that also are enjoyed by recreational beach-goers. Cryptic coloration of piping plover adults, chicks and eggs is advantageous to avoid predation, but makes it nearly impossible for them to be avoided on busy beaches. Beach visitors can inadvertently trample nests and/or chicks, particularly when driving down the shoreline, or cause nest abandonment because of repeated disturbance. Increased human activity following the establishment of Presque Isle State Park in 1929 likely led to abandonment of the site by nesting piping plovers in the mid 1950s. Potential disturbance by recreational beach-users still is a major threat to nesting plovers and other shorebirds, however, several management practices reduce these risks significantly where nests are found (see Management Programs). Additionally, nesting birds and their young are vulnerable to terrestrial and avian predators, such as foxes, coyotes, feral cats, crows, gulls, merlins, and owls. Nesting habitat is not threatened by development in Pennsylvania as in other parts of the piping plover’s breeding and wintering ranges. Rather, degradation from vegetation encroachment is a primary concern. Emerging issues throughout the Great Lakes, such as Type E botulism and off-shore wind turbines, also pose risks to this fragile population.

Management Programs: Piping plovers, particularly in the Great Lakes population, are one of the most intensively managed endangered species given their small breeding populations and high vulnerability to disturbance. Nests are protected by predator exclosures that allow entry and exit for the plovers but deter predators. These exclosures are coupled with a larger "closed area" that enables the birds and their chicks to forage safely without disturbance. Plover guardians keep track of the nests daily, noting when birds were first seen, when eggs were laid, when they hatched, and how many chicks fledged. Since 1993, individual plovers (adults and chicks) have been marked with uniquely colored leg bands to better understand movements of breeding birds within the breeding range and between the breeding range and the wintering areas, survivorship, mate retention, and dispersal.

The Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan identifies several conservation objectives for this species. To that end, the Pennsylvania Game Commission has been working with the state Department of Conservation and Natural Resources' Bureau of State Parks, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, Erie Bird Observatory, and other partners to monitor the birds and evaluate habitat at Presque Isle State Park. The State Park's management plan is one of the few in the historic range of the Great Lakes population to outline specific management tasks for piping plovers. It is due to the strong partnership between federal, state, and local entities that Pennsylvania was well-positioned to be successful upon their return as breeding birds in 2017.

How you can help

- Share the shoreline. Obey all closed area signs posted on Presque Isle State Park beaches, and other beaches as you travel. Give wildlife the space they need to feed, nest, and raise young.

- Pack it out. Leaving trash behind is a wildlife hazard and invites potential predators.

- Leash up. Dogs love the beach and we love dogs! But an unleashed prey drive can overwhelm beach birds. Make sure you know which beaches allow dogs and always keep Fido on a 6-foot leash.