Short-Eared Owl

Species Profile

Scientific name:

Asio flammeus

Owl Wildlife Note (PDF)

Print

Print

Current Status: In Pennsylvania, the short-eared owl is endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. Although not listed as endangered or threatened at the federal level, the short-eared owl is a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Migratory Bird of Conservation Concern in the Northeast and a Partners in Flight North American Landbird Conservation Plan priority grassland species. All migratory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.

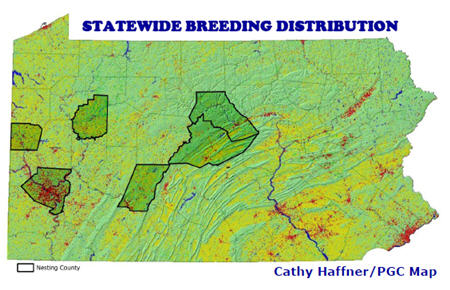

Population Trend: In Pennsylvania, short-eared owls (Asio flammeus) are at the southern edge of their North American breeding range. They may be found regularly during winter throughout the state, but numbers vary from year to year depending on prey densities. It is more common as a wintering bird of farmlands and wetlands. They have been found nesting on reclaimed strip mines in western Pennsylvania, from the Piney Tract Important Bird Area in Clarion County south to the Imperial Grasslands in Allegheny County, and scattered reclaimed strip mines in the central part of the state. However, nest sites are rarely documented to be active for more than a few years in succession. The 2nd Pennsylvania Breeding Bird Atlas (2004-2008) yielded only one confirmed breeding record and three records that indicated the species was 'probably' nesting at that location. In total, short-eared owls were observed in only seven atlas blocks (out of 4,937), illustrating how rare the species is in the state. The short-eared owl was designated endangered in 1985's Species of Special Concern in Pennsylvania, published by the Pennsylvania Biological Survey. It remains on the state endangered species list given its small breeding population and limited distribution.

Identifying Characteristics: The short-eared owl received its name from its diminutive "ear" tufts. It is about the size of a crow, 13 to 17 inches high, and has a 38- to 44-inch wingspan. Color is variable, from light to dark brown. Dark circles surround their eyes. The dark, crescent-shaped patches on the undersides of its wings, dark wingtips, and large buffcolored patches on the upper sides are very distinctive in flight. These field marks help to distinguish it from the barn owl, a species whose hunting habitat is similar to that of short-eared owls. Barn owls are very light in color, slender birds with a larger wingspan than short-eared owls and have a heart-shaped, rather than round, face. In flight, short-eared owls will vocalize a very raspy bark that sounds a bit like a terrier flying overhead. In courtship, males give subdued deep hoots while in flight and clap their wings in a flight display. This open county owl has a distinctively slow and buoyant flight while hunting, like a giant moth flying low over the fields. They quarter the fields methodically and then fly up in loops and hover over potential prey before dropping on the mouse or soaring to their next hunting ground.

Atypical for owls, shorted-eared owls nest on the ground, sometimes in colonial groups. The female excavates a slight bowl-shaped depression, often at the base of a clump of weeds or grasses, and sparsely lines it with grass and feathers. Nesting typically occurs during May and June. The female, which incubates the eggs while the male brings her food, is reluctant to leave the nest, thus making searching for this species particularly difficult. A typical clutch consists of four to seven white eggs. Young hatch about three weeks after egg-laying, and are able to fly in about a month. The female is the primary caretaker of the young. Throughout the nesting and brood-rearing periods, the male defends the territory and brings food to the female and the young. By late September–October, breeding birds may migrate to their southern wintering grounds in the southern United States or northern Central America. If prey is readily available and the winter is mild, short-eared owls may overwinter in the state. The tall grasses on the periphery of the Philadelphia Airport attracted dozens of wintering short-eared owls until the late 1980s. They also are attracted to larger open fields and reclaimed strip mines at various parts of the state including the southern tier of counties. Short-eared owls will roost during the day in dense vegetation on the ground, sometimes under the dense lower boughs of a conifer.

Unlike most other owls, the short-eared is active at dusk, dawn and – at times – even in midday; therefore, they are seen more often than other owl species. In winter, they hunt large open fields of tall grasses and reclaimed strip mines. They usually take the "second shift" of rodent hunting when the harriers go to their night roost. The exchange between harriers and short-eared owls is like a graceful aerial ballet of diving and chasing not to be missed.

Preferred Habitat: Short-eared owls inhabit reclaimed strip mines, open, uncut grassy fields, large meadows, airports and occasionally, marshland. In agricultural areas, they are attracted to CREP fields and other areas with tall winter grass. Short-eared owls are more likely to be encountered here in the winter when several may be seen together, hovering or flying low and in circles over agricultural fields in search of their main prey, meadow mice.

Reasons for Being Endangered: Short-eared owls have declined across their range as suitable breeding and wintering habitat, namely grasslands, marshes, and infrequently-used pastures, have been lost to development, converted to more intensive agricultural practices, or altered through a field's natural succession to forest. In Pennsylvania, suitable nesting habitat for the short-eared owl is extremely limited and intensive agricultural practices make many potential habitats unsuitable.

Management Programs: In Pennsylvania, most open lands are farmlands that are subjected to repeated disturbance. Accordingly, the welfare of grassland nesting birds is threatened. This may be why the only known nests of short-eared owls were discovered in extensive and low-disturbance open lands, such as a strip-mine reclaimed to grass. Future management, based on the needs for safe nesting habitat for all grassland nesters, should include the creation of large, herbaceous reserves suitable for all grassland nesters. Such reserves might include airports, reclaimed strip-mines and large pastures. Primary management of these areas must assure a disturbance-free nesting season. Several sites that have supported nesting short-eared owls and wintering owls have been designated as Important Bird Areas.

Sources:

Master, Terry L. 1992. Short-eared Owl. In Atlas of Breeding Birds in Pennsylvania (D. Brauning, Ed). University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA. pp. 164-165.

McWilliams, G. M. and D. W. Brauning. 2000. The Birds of Pennsylvania. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

Pennsylvania Game Commission and Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. 2005. Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan, version 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008.

Birds of Conservation Concern 2008. United States Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory Bird Management, Arlington, Virginia. 85 pp.

Wiggins, D. A., D. W. Holt and S. M. Leasure. 2006. Short-eared Owl (Asio flammeus),

The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Suggested for Further Reading:

Askins, R. A. 2000. Restoring North America's Birds. Yale University Press. New Haven and London.

Duncan, J.R., D. H. Johnson, T. H. Nicholls, eds. 1997. Biology and Conservation of Owls of the Northern Hemisphere. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report NC-190. North Central Research Station, St. Paul, Minnesota.

Johnsgard, P. A. 1988. North American Owls: Biology and Natural History. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D. C.

NatureServe. 2009.

NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Search for "short-eared owl."

Partners in Flight United States: Pashley, D. N., C. J. Beardmore, J. A. Fitzpatrick, R. P. Ford, W. C. Hunter, M. S. Morrison, and K. V. Rosenberg. 2000. Partners in Flight Conservation of the Land Birds of the United States. American Bird Conservancy, The Plans, VA.

Pennsylvania Game Commission and Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. 2005. Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan, version 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Rich, T. D., C. J. Beardmore, H. Berlanga, P. J. Blancher, M. S. W. Bradstreet, G. S. Butcher, D. W. Demarest, E. H. Dunn, W. C. Hunter, E. E. Inigo-Elias, J. A. Kennedy, A. M. Martell, A. O. Panjabi, D. N. Pashley, K. V. Rosenberg, C. M. Rustay, J.S. Wendt, T. C. Will. 2004. Partners in Flight North American Landbird Conservation Plan. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Ithaca, NY.

Rosenberg, K. V. and J. V. Wells. 2005. Conservation priorities for terrestrial birds in the Northeastern United States. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report PSW-GTR-191.

By Cathy Haffner and Doug Gross

Pennsylvania Game Commission

8/19/2014