2020 Summer Intern Log

Interested in a career or volunteer position with the Pennsylvania Game Commission?

July 27 – Week 6, Bows & Arrows & Guns, Oh My!:Adventures w archery and firearms

By Jordan Sandford

This was a very busy and exciting week. We attended an archery training at the Ross Leffler School of Conservation, the Game Commission's training school located in Harrisburg, and headed to the gun range to familiarize ourselves with several different types of firearms. Read on and delve deeper into our adventures!

NASP in Harrisburg

On Tuesday, Mikayla and I headed up to Harrisburg with several other PGC interns and Lauren to attend a NASP training with Todd Holmes. NASP stands for National Archery in the Schools Program. NASP's mission is to promote instruction in international-style target archery as part of in-school curriculum, to improve educational performance and participation in the shooting sports among students in grades 4-12. During our training, we learned range safety and set up, how to determine eye dominance, how to use a string bow to establish proper draw length, the 11 steps to archery success, how to properly run a range, and bow nomenclature. We had the opportunity to practice, shoot, and familiarize ourselves with the bow and arrow. That's Mikayla posing with her bullseye shot! After some fun archery games, we took a test and officially became certified NASP instructors. This means that we can now run our own archery program and range. We both enjoyed this training very much. It was very cool to understand how a bow works and see the fruits of our labors displayed on the target. Consistency and practice produce results!

Gun Range

On Thursday, we joined Dan Lynch, Lauren Fererri, and Dustin Stoner at a Game Commission gun range for some target practice. Prior, Mikayla had no experience with guns or hunting, and I had been out hunting with my dad a handful of times, but never fired a weapon myself. Regardless, we were both excited to try something new. Dustin gave us a lesson on firearms safety and made sure we were comfortable. We learned three main rules to remember when handling firearms: 1 – treat every firearm as if it is loaded, 2 – always practice muzzle discipline (this means to always, ALWAYS, be conscience of where your gun is pointed), and 3 – never put your finger on the trigger unless you are about to shoot. It is always important to keep your finger outside the trigger guard, unless you are firing. This helps reduce accidents and keep everyone and everything around safe. At the end of the day, we had the opportunity to shoot several different types of firearms. We fired a .22 revolver handgun, a .357 semi-automatic Glock, a .22 rifle, a .270 rifle, and a .20-gauge semi-automatic shot gun. We fired both free hand and using a gun bench. My favorite was shooting the .22 because it had little to no recoil. After completing our hunter education course, we both are very excited to get out and try hunting with our mentors!

Thanks so much for tuning in to this week's log! Keep an eye out for what fun stuff we get into next week.

July 20 - Week 5, Still Hanging in There: Adventures with Bat Acoustics, Bat Counts and Kestrel Banding!

By Mikayla Traini

Welcome,‘bat’! Jordan and I had another jam-packed week at the Game Commission. This was another bat week! We helped Dan Mummert, a wildlife biologist with a bat acoustics study, and helped Dan Lynch with another bat count as a continuation of our first count. We also helped Lauren Ferreri band kestrels again, this in Lehigh County at State Game Lands 205. And this time, we found something EXTRA special.

Bat Acoustics

We began our adventures this week with Dan Mummert. We met at Middle Creek at 7:30PM, then drove to Lititz for the bat acoustics study. We parked in a church parking lot until 9PM, when the study started. We set up our equipment while we waited. First, we attached a magnetized device to the roof of the truck to record frequencies of the bats flying overhead. It had a cord that led into the vehicle and connected to a laptop.

The laptop software allowed us to see a map of our route. We drove about 20 miles going 20 miles an hour—approximately one mile per minute. Jordan and I took turns telling Dan when and where to turn. It tracked our location as we drove. On the left of the screen was the sonogram for the bat acoustics. It showed the frequencies of the bat noises being picked up by the device on the roof of the vehicle and reproducing the sound back out of the speakers for us to hear. Each species of bat makes sounds at a different frequency. By recording the frequencies, we could determine the species.

Bat Count: Part 2

On Thursday, we joined our mentor, Dan Lynch once again to do a bat count at the location in Oley that had the most bats on our first count. On our first count, there were 167 bats, including adults and pups. We repeated the same bat-counting process. We hiked out with our lawn chairs and flashlights just before 9PM to await the evening feast. Soon, bats began flying out of the box to hunt for their dinner. After half an hour of waiting and counting, we found that many new bats had arrived and that pups had begun to fly! There were two bat boxes at this location. This time around, the box that had 167 bats last time had 189—22 more bats than last time. In the other box, last time there were less than 20 bats. But on Thursday, there were 81. Quite an increase in bat count at both boxes.

Kestrel Banding in Lehigh County

Once again, we found ourselves out with Lauren Ferreri banding kestrels. However, this week we were in Lehigh County at State Game Lands 205. This box is actually not a kestrel box. It is a barn owl box, similar to the boxes we saw in Week 1 with barn owl banding. This box had been taken over by kestrels. But sadly, a swallow had built her nest on top of the kestrel nest, causing the mother kestrel to abandon the nest and preventing the kestrel eggs from surviving.

At another box, we were pleasantly surprised to find a mother kestrel still in the nest. Very carefully, Lauren retrieved the mother from the nest who was on very young chicks. Once she was retrieved, we saw that she was banded. We checked the band and found the serial number in Lauren’s notes! Lauren had banded this bird at Middle Creek two years ago when the bird was one year old. It was really interesting to have a recapture while banding.

Lauren noticed that the band was not as tight on her leg as it should be. So, in the same manner that we tighten the bands on newly banded birds, she tightened the band around the adult kestrel’s leg. For an adult, the bird was pretty well behaved and did not fight too much. You can see by the feather coloration how much more developed this bird is than the kestrel chicks we banded in Week 1. Colors are much brighter and more vibrant.

A brood patch will often appear on their lower abdomens of mother birds when they are on eggs. A brood patch is a bare patch of skin on a bird’s abdomen that makes transfer of heat from the adult to the eggs much more efficient. The mother bird intentionally plucks feathers out of this spot to provide warmth for her eggs.

Thank you so much for reading our log this week! We hope you enjoyed our continuation of bat studies and kestrel banding. Join us next week for ‘Bows and Arrows and Guns, Oh My! Adventures with Archery Firearms’.

July 13 – Week 4, Wild About Wings: Adventures in preparing duck wings!

By Jordan Sanford

It was a slow week at the office so Mikayla and I have made ourselves busy with a project Dan assigned to us on the very first day: WINGS! Dan recently came into possession of roughly 300 different species of waterfowl wings. They are all labeled, packaged and "chillin" in a freezer. Our job is to dissect these wings, strip the bones of the meat and muscles, and prepare them for educational uses. I thought it would be a fun topic to take you on step-by-step, so here we go!

STEP 1: Materials and set up

First things first, we needed to prepare our workspace. We started out by grabbing a large piece of black foam board. This is what we use to dissect on and pin the wings to, while also protecting the tabletop. Next, we set up our tools. Pins, to secure the wings to the board after they are thoroughly cleaned. And a knife, tweezers, bottlenose pliers, and Borax. The knife, to slice through feathers, meat, and muscle. The tweezers and pliers, to pull out debris and clean up the bones. The Borax, for preservation purposes – to dry any remaining meat and the bones, and to prevent bugs from eating away at the wing. Also, nitrile gloves we wear constantly to protect ourselves. Finally, and perhaps the most important step of preparation, is your choice of music. Mikayla and I have differing tastes in music, but one thing we can agree on is... Classic Rock rules all. There's nothing like dissecting a bird wing to the tune of "Kickstart my Heart" by Motley Crue or "American Woman" by The Guess Who. Okay, we are ready to start.

STEP 2: "GET TO DA CHOPPA" - us, getting ready to slice some bird meat.

Okay, you have your tools, you have your gloves, you have your tunes. You're ready to chop. We found it easiest to start the first cut along the curve of the wing. The feathers are thick here, but once you cut enough of them away, the meat and bone are exposed. The next part is simple. You just cut away at the meat and muscle, slowly taking it off the bone and carefully removing it from the skin. You must be careful not to recklessly slice through everything or you will pierce the skin to the other side and the outer feathers will look disheveled… *ahem* Mikayla *ahem*. Once you have removed enough of the meat, muscles, and ligaments, you're ready to Borax and pin. A finished wing can be spread out on a clean piece of foam board. We used small cardboard pieces to hold the spread, dissecting pins to secure the cardboard to the wing, and the wing to the foam board. Once the wing was pinned, we applied a generous amount of Borax to the exposed bones of the wing, and used tape to label it. This wing is that of an immature male Northern Shoveler. Once our foam board was full of Borax-ed wings, we placed it in a warm, dry spot and let it sit for about two weeks, providing the Borax time to dry out the bones and any remaining meat or muscles. Then it was on to the next step: spraying with rubber!

STEP 3: Spraying with Rubber

Once the wings had sufficient time to dry, it was time to seal them. First, we dumped the excess Borax off the wing, into the trash. Then, we used a medium-sized paint brush to remove any remaining Borax left in the crevices of the wing bones. The next part was spraying with Plasti Dip. This multipurpose rubber coating is meant to seal the exposed bones and prevent any insects from eating the wing or laying eggs inside it. It is important to try to spray just the bone area and not the feathers of the wing. Do this in a well-ventilated area or you will become under the influence of the fumes. We are NOT speaking from experience. Once finished, the waterfowl wings can be used for a multitude of educational purposes.

BONUS CONTENT: Meeting at Middle Creek, Dove Banding, and Trail Cam update!

While we spent most of the week working on wings at the Southeast Region Office, we also had the special opportunity to interact with several other agency employees at a strategic planning meeting for Middle Creek. At this meeting, Joe Monfort, environmental education specialist at Middle Creek, and Bill Williams, information and education supervisor in the Northeast Region, led our team through various presentations and workshops outlining statistical information about visitation to the center, different programs we already or should plan on offering, and hands on activities discussing Middle Creek's vision and mission. It was a very insightful and inspiring meeting to attend; we had a first-hand experience of seeing how large of a role the several different stakeholders and user groups play in the decision-making process at Middle Creek. Overall, it was a very cool experience for Mikayla and me.

Friday, we joined Lauren Ferreri and fellow interns Alysha and Dan for some field experience banding doves. Much like with kestrels, barn owls, and geese, dove banding followed very similar guidelines. Doves take a size 3A band. The doves were aged based on coloration and the edging present on their wing tips, and sexed based on coloration. The adult females are drabby brown in color, whereas the males have a slate blue head and rosy breast. We also record the molt for the doves.

After dove banding in the morning with Lauren, we collected the SD cards from our trail cameras and brought them back to the shop to see what kind of footage we got! We saw a LOT of deer, coyotes, woodchucks, geese, raccoons, opossum, great blue herons, and several other species. Some trail cameras produced better footage than others. On a few, we got 350 pictures of all grass and vegetation moving in the wind. While these images are kind of boring, they are useful because it lets us know maybe we need to relocate or reposition that camera. Overall, for a first trial run of the trail cams, we were very pleased with our results. Keep checking back in with us to see what other fun images we may capture!

Thanks for hanging out with us this week! Tune in next week to see what kind of fun stuff we may get in to.

July 6 – Week 3, Hanging With the Bats: Adventures with Bat Boxes & Trail Cameras

by Mikayla Traini

Jordan and I are back again for another week as Education Interns at the Pennsylvania Game Commission, Southeast Region. This week was a shorter week for us because it was July 4th weekend. On Monday and Wednesday, we did some housekeeping at the Southeast Region Office – preparing bird wings, creating wildlife challenges, and a bit of reorganization. The real fun started on Tuesday when we came into work at 2pm. Yes, you heard me right, 2pm. How are we fitting our 8-hour workday in? We work till 10pm! But don’t worry, we don’t usually work crazy hours. On Tuesday we were checking the bat boxes!

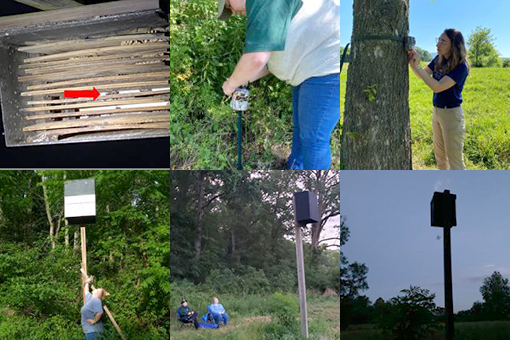

Bat Boxes

Bat boxes are man-made homes made specifically to encourage bat nesting. These wooden or metal structures can be placed in a variety of locations, like on the side of a house, a barn or on a free-standing pole like the one pictured. These bat boxes have horizontal baffles inside to allow the bats to comfortably hang inside the box. The bottom of the box is open to allow the bats to enter and exit the box as they please.

Our task was to perform an Appalachian bat count within the bounds of Oley Township. With our mentor, Dan Lynch, we drove around to eight bat boxes and checked for bats. When checking the boxes during the day, a flashlight was directed up through the rafters from the open bottom. Once the area was illuminated, we checked to see if there were any bats resting in the baffles.

The red arrow in the image, indicates bat pups visible in the lower right-hand corner of the box. Once counted, the number is recorded. Unfortunately, most of the bat boxes that we visited had no bats. We did, however, find a mouse in one bat box! This was very unusual, and we speculate it just wanted to ‘hang out’ for a little bit in the box before returning to his nest.

The last bat box on our agenda was a box that has a history of being a very successful location. Since this box has been known to house as many as 200 bats at once, we needed a different counting strategy. We arrived just as the sun was setting, around 9 PM. Since bats are nocturnal and do their insect hunting at night, as soon as the sun began to set, all the bats began to fly out of the box. They generally fly out one at a time or in very small groups. This is useful because it allows us to count them as they come out of the box. As we sat in silence watching the box, we counted 136 adult bats fly out of the box. Once a decent amount of time had passed and we had seen no more bats, we assumed that only the pups were left in the box. We then walked over to the box and shined the flashlight into the baffles. We counted 32 pups. In total, we found 168 bats at this location!

This is good news considering how important bats are to our local ecosystem. The bats in Pennsylvania are insectivores, while most tropical bats are frugivores. A bat can consume up to 25 percent of its weight in a single feeding. For this reason, bats are a great natural form of pest control for crops and fields. This allows farmers to rely less on chemical substances for managing pests. The importance of doing these Appalachian Bat Counts is to have a better idea of the prevalence of bats in the area as well as an indication of potential pest control.

Trail Camera Study

This week, we finished setting up our trail cameras. As discussed in last week’s log, our trail camera study is based on waterfowl nest predation and we have 12 cameras in total. When choosing the set-up locations, Tyler Hudock, a game lands maintenance supervisor at Middle Creek, gave us helpful tips and advice on good locations. For the most part, we chose the locations on our own. The secret formula for catching wildlife on trail cameras is simple. First, you don’t want your camera in a high human traffic area such as a trail or road. Since the trail cameras are motion activated, they will take pictures of anything moving within 80 yards. The goal is to capture wildlife, not humans. Instead, it is best to set them up in areas that are out of sight from hikers or passersby. The second step is to ensure that your spot has the ‘Big Three’: field, forest and water. The “point” where the field meets the forest and/or waterbody is typically a high traffic area for the wildlife we are trying to capture. The third and final step is to make sure the camera is not facing East. Though this may seem obvious, it is important to remember that if you catch movement on camera in the morning when the sun is rising, you are still able to see the image and not a giant blurb of sun.

We placed trail cams on metal stakes and around trees depending on what worked better for the location. We planned to head back to Middle Creek a week later to see what our cameras captured. We can always adjust if the angle is too high or fix the orientation of the camera. If we have not captured anything of interest to our study, we may move our cameras to different locations that we think may offer better results. Once we have found the right locations and orientations for our cameras, our study will officially begin. Right now, it is all an educated guessing game and working out the kinks. The length of the study is not official yet, but we think it would be a good idea to capture for at least one to two months. This will provide us with a good pool of pictures for our study. Hopefully we will find what we are looking for.

We’ll be back next week discussing preparing bird wings for education and more.

June 29 - Week 2,

What’s all the honking about: Adventures with Goose Banding and Trail cams!

by Jordan Sanford

Hey y’all! My name is Jordan Sanford and I have recently graduated from Mansfield University with a B.S. in Environmental Biology. I heard about this internship opportunity through one of my advisors at school and I had to jump on it! Once I received the good news that I got the position I packed up my car and moved four hours from home to start up my life down here in Pennsylvania. I had such a blast our first week with the Game Commission, learning and experiencing tons of cool things in the field with Mikayla. This week we had the opportunity to help out John Morgan, our regional wildlife management supervisor here in the Southeast Region, with a goose roundup, work with Lauren Ferreri and fellow land management intern Alysha Ulrich to set up dove traps, and work on our own independent trail camera study. Keep reading for all the juicy details!

Goose Roundup

On Wednesday, June 24th, Mikayla and I joined several of our coworkers at Middle Creek for a goose roundup. What’s a goose roundup you ask? Well, it’s exactly what it sounds like! We all converged in the field next to the lake at Middle Creek. Three of us were in kayaks out on the lake and pushed the geese onto the land where the rest of us were waiting with netted panels. We slowly formed a perimeter around the geese, and walked inwards with arms outstretched. Eventually, the circle was small enough for the panels to be connected with ties and the geese were successfully enclosed. From there, two biologists, Dan Mummert and Ken Duren entered the “Goose Arena” and began searching for goslings.

The goslings were separated into a smaller pen adjacent to the larger enclosure. Lauren and Steve Ferreri sexed and banded the young geese and released them back towards the water. Meanwhile, Dan and Ken were on the hunt for already banded geese. These geese are called “recaps” because they were previously captured and banded at a different time, so we did not need to band them again. Once all the goslings and recaps were recorded and released, several of the biologists hopped in the pen and began sexing and banding the geese. Geese take a size 8 band.

It is important to sex the geese because males get a different band than females. To sex a goose, one must first get the goose onto its back. Then, you slowly brush against the grain of feathers near its rear end, until the circular vent is exposed. If a worm-like project is exposed, the goose is male. If two small bumps appear, the goose is a female. After the geese were sexed and banded, they were released back towards the water.

This is where we come in. In addition to filming the goose roundup for other media opportunities, Mikayla, the other interns, and I were in charge of making sure the released geese headed back towards the water’s edge. A few geese were disoriented and started heading towards the road or up the hill into the meadow, and we would circle around in front of them and direct them back the right way. At the end of the day, there were 93 recaps and 261 newly banded birds.

Dove Traps

Later in the week, Mikayla and I teamed up with Lauren and Alysha at Middle Creek to learn about doves. We found out that there was a dove hunting season here in Pennsylvania which runs from Sept. 1 through Nov. 27, and then Dec.18 through Jan. 2. We also found out that the Game Commission manages for dove fields statewide. These are fields specifically planted with attractive foods like sunflowers and millet, as well as managed for other habitat components like water and grit, to attract doves. We are trapping and banding the doves to track mortality rates, and compare mortality via hunting and migration.

Alysha, Mikayla and I worked with Lauren at the dove fields by laying the traps out upside down, so the doves would get used to them being there, and putting out safflower seed to attract them.

Mikayla used a tool to rake and level the disk strip. I put out piles of safflower for the doves. Alysha tagged the traps with orange flags so when our crew goes out to mow or perform general maintenance on the fields, they don’t run over the traps, potentially harming doves. We had a great time with Lauren and Alysha learning all about doves.

Trail Cameras

One of our first assignments as interns was a trail camera research study. Our mentor, Dan, outlined the basics of the study, but left a majority of the details and planning up to us. The study is based on waterfowl nest predation at Middle Creek. We know there’s a surplus of nest predators, but following a trapping survey, the amount of predators caught and the amount of predation we were seeing did not add up. So Mikayla and I are in charge of putting up several trail cameras throughout the game lands surrounding Middle Creek to try and see where the predators are most prevalent, and what types of predators we have the most of. We worked closely with Tyler Hudock, a Game Lands Maintenance Supervisor at Middle Creek, to find the best areas to observe. He informed us of one area where there may be a coyote den, and another area where there may be river otters. We were sure to place a camera near a log crossover, a natural walkway animals may use to travel. Tyler was super helpful with setting up the cameras, placing the lures, and just giving us some general advice and tips. We have placed six cameras so far, and are very excited to check back and see what kind of footage we get. Thanks for reading, and tune in next week to see what kind of shenanigans we may get ourselves into!

June 22 - Week 1,

Welcome: Adventures in Kestrel and Owl Banding

by Mikayla Traini

Hello from the Pennsylvania Game Commission! My name is Mikayla Traini and I am an Environmental Science student at Drexel University, working as an Environmental Education Intern this summer in the Pennsylvania Game Commission's Southeast Region. Jordan Sanford is the other intern, a recent graduate of Mansfield University with a B.S. in Environmental Biology. Our advisor and mentor is Mr. Daniel Lynch, a Wildlife Education Specialist in the Southeast Region. Though this summer is going slightly different than planned (thaaaanks Coronavirus), we are excited to be starting our internship and can't wait to have a wide variety of experiences in the field.

In our first week as Environmental Education Interns, we did what most interns do. We set up our desk space, struggled through the extensive on-boarding process, met people around the office, banded baby kestrels and owls...wait, most interns don't do that? Our job is a bit more interesting than your average internship. I hope you stick around to see our adventures throughout the rest of the summer!

Kestrel Banding: Under the supervision of Lauren Ferreri, Biological/Visitor Manager at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area, we observed and learned how to band kestrel and owl chicks. On Wednesday, we spent the day at Middle Creek Wildlife Management Area checking American kestrel boxes for chicks younger than 25 days old. Once they are about 30 days old, they are fully grown and ready to leave the nest. In general, they are banded between 14 and 25 days old to ensure their legs are large enough, but they are not able to fly away.

As a reminder, only certified banders who hold banding permits are allowed to band birds. We were accompanied and instructed by Lauren Ferreri, a certified bander, while assisting in banding these birds. Do not try this at home if you are not a certified bander. For purely educational purposes, I will briefly discuss the banding process.

Our first step in banding these chicks was to remove them from the nest. This was no easy task, considering the kestrel boxes sit atop a post about 10 feet high! Carefully ascending the ladder, one by one the chicks are lifted from the box and into a fabric bag to be transported to the truck bed for banding.

Once we returned to the truck, it was time to start the banding process. There is a wide variety of bands, of all different sizes, for various bird species. All bands are sized to ensure the fit around the bird's leg is comfortable, without inhibiting growth or flight. For example, a bald eagle will take a larger size band (size 10) than an American robin would (size 1A). American kestrels require a size 3A band to properly fit around their leg. For each size band, a special type of pliers is used to band the bird. It has the ability to open the band to the proper width to be fit over the bird's leg. The pliers close the band around the bird's leg just enough to secure the band, to avoid injuring the bird.

You may be asking yourself, why is it important to band birds in the first place? From a conservation and management standpoint, it is important to band birds to observe their dispersal patterns, or how far they will go from where they were born, and migratory habits. On each band, there is a band number unique to that individual bird as well as the website of US Geological Survey Bird Banding Lab in Maryland. If, for example, a bird with a band is found dead on the side of a road and someone finds it, they can contact the Bird Banding Lab and provide them with the band number and the location where the bird was found. This information can then be compared to previously collected information on that bird species, adding to the database. Information like this is of HUGE importance to the research community!

After the band has been placed on the bird, the bird is weighed and compared to a photo book to determine its approximate age. We estimated that the chicks banded at Middle Creek were about 17 days old. Like most other raptors, adult male kestrels are smaller than female kestrels. Adult male kestrels average about 110 grams while female kestrels average closer to 130 grams. This is equal to about 3/10ths of a pound.

You can differentiate the female and male kestrels by the color of their feathers. This is called sexual dimorphism, or distinct differences in males and females based on size or appearance. In the case of the kestrel, females (below on left) generally are all brown with dark brown barring on their feathers while males (below on right) have more of a bluish-grey tint to them. Likewise, female kestrels have brown tail feathers with dark brown barring, whereas males have plain brown tail feathers with a black band. Once the kestrel chicks were banded, we ascended back up the ladder and carefully placed them back in their nest, all before the mother got back!

Barn Owl Banding: In addition to banding kestrel chicks, we also had the opportunity to observe the banding of young barn owls. Check out the

Wildlife on Wifi segment "Barn Owl and America Kestrel Research From the Field" at

www.pgc.pa.gov if you are interested in seeing our adventure for yourself! The barn owl box was located at a privately owned farm in rural Lancaster County.

The process of banding these chicks was almost identical to banding the kestrels. The main difference is the size and type of band used. While the kestrel used a size 3 band, the barn owl uses a size 6 or 7A band because of the larger diameter of their leg. It is also best for these birds to have lock-on bands to prevent them from ripping the band off with their beak. Kestrels do not exhibit the behavior of removing the band, so a simple butt-end band without locking mechanisms suffices.

Another difference in our process for barn owls was the way their ages are estimated. Instead of using a picture guide, their wing feathers are measured in order to age them based on known values from previous research. According to our measurements, this young barn owl is estimated to be about 25 days old. Barn owls take approximately 10 weeks to fully develop before fledging the nest, and these little guys and gals are about halfway there.

Thank you so much for reading our first ever Pennsylvania Game Commission Environmental Education Intern blog! I hope you enjoyed learning about the experiences we had this week in the field. Keep an eye out for our next blog and find out what all the HONKING is about in "The Wild Goose Chase: Week Two Adventures with Canada Goose Banding".